Here, stretched in ranks, the swelled swarths are found.

Sheaves heaped on sheaves here thicken up the ground.

With sweeping stroke the mowers strew the lands—

The gatherers follow and collect in bands;

The rustic monarch of the field descries,

With silent glee, the heaps around him rise."

-- from Homer's "Iliad", A. Pope translation

All material quoted from:

The book of the farm: detailing the labors of the farmer, steward, plowman, hedger, cattle-man, shepherd, field-worker, and dairy maid, Volume 2, by Henry Stephens, 1852,

Chapter 34 (page 373 onward)

In mowing, it is the duty of the mower to lay the cut corn [meaning "grain"] or swath at right angles to his own line of motion, and the straws parallel to each other...To maintain this essential requisite in corn [grain]-mowing, he should not swing his arms too far to the right in entering the sweep of his cut, for he will not be able to turn far enough round toward the left, and will necessarily lay the swath short of the right angle; nor should he bring his arms too far round to the left, as he will lay the swath beyond the right angle; and, in either case, the straws will lie in the swath partly above each other, and with uneven ends, to put which even in the sheaf is waste of time. He should proceed straight forward, with a steady motion of arms and limbs, bearing the greatest part of the weight of the body on the right leg, which is kept slightly in advance...The sweep of the scythe will measure about 7 feet in length, and 14 or 15 inches in breadth.

The woman-gatherers follow by making a band from the swath, and laying as much of the swath in it as will make a suitable sheaf...The gatherer is required to be an active person, as she will have as much to do as she can overtake. The bandster follows her, and binds the sheaves in the manner already described, and any 2 of the 3 bandsters set the stooks together, so that a stook is easily made up among them; and in setting them, while crossing the ridges, they should be placed on the same ridge, to give the people who remove them with the cart the least trouble.

Last of all comes the raker, who clears the ground between the stooks with his large rake of all loose straws, and brings them to a bandster, who binds them together by themselves, and sets them in bundles beside the stooks. This is better than putting the rakings into the heart of a sheaf, where they will not thresh clean with the rest of the corn; and, moreover, as they may contain earth and small stones, and also inferior grain, from straws which may have fallen down before the mowing, it is better to thresh bundles of takings by themselves.

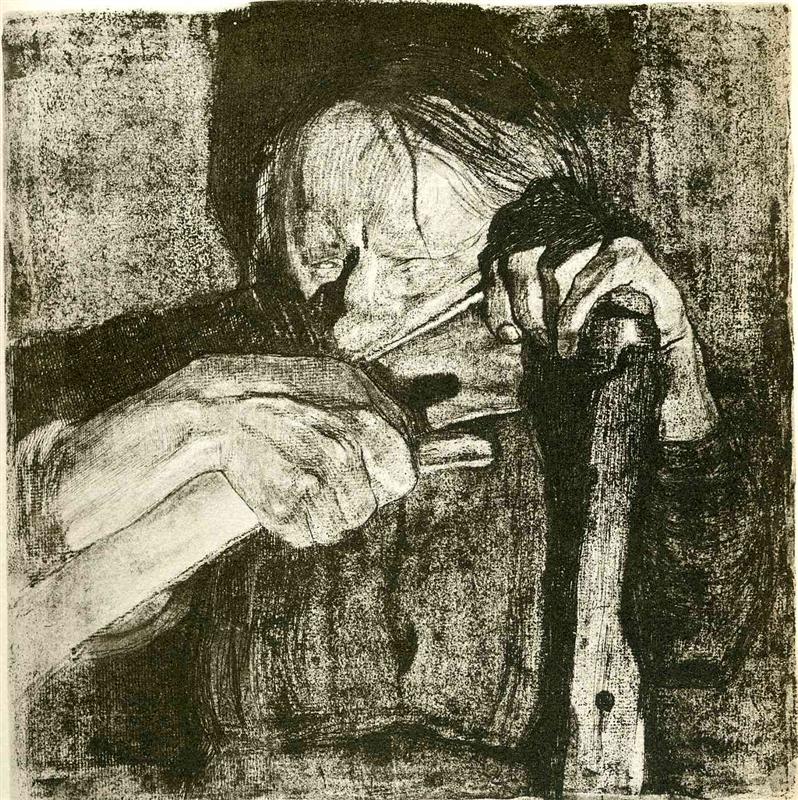

The figure [above] exhibits the 3 kinds of scythes in operation [along with the other workers doing the described tasks].

A scythesman will cut fully more than 1 imperial acre of wheat in a day. Many farmers affect to believe that the scythe is an unsuitable instrument for cutting wheat; but I can assure them, from experience, that it is as suitable as the sickle, and that mown sheaves may be made to look as well as reaped. No doubt mowing wheat is severe work, but so is reaping it. Of oats, 1 scythesman will mow fully 2 acres with ease. The oat crop is remarkably pleasant to handle in every way; its crisp straw is easily cut by the scythe, and being hard and free, and generally not too long, is easily bound in sheaf and set in stook. Nearly 2 acres may be mown of barley; but the gummy matter in the straw, which gives it a malty smell, causes the stone to be frequently used in mowing barley, and the straw being always free, the bands are apt to break when rashly handled in binding the sheaves.

The expedient of gaiting, however, is only practiced in wet weather, and even then only should the crop, if allowed to stand, be endangered by a shaking wind. It is confined also to a particular kind of crop, namely, oats—wheat and barley never being gaited, because when wheat gets dry, after being cut in a wet state, it is apt to shake out in binding the gaits; and when barley is subjected to the rough usage of binding, after being won, the heads are apt to snap off altogether, and, besides, exposure in gaits would injure its color, and render it unfit for the maltster. Oats are protected by a thick husk, and the grain is not very apt to shake out in handling, excepting potato-oats, which are seldom gaited, the common kinds only being so treated. But, for my part, I would not hesitate to gait any sort of oats when wet with dew in the morning, or even when wetted with rain, rather than lose a few hours' work of reaping every morning, or at nightfall.

Gaits, it is true, are very apt to be upset by a high wind; but after having got a set, it is surprising what a breeze they will withstand. After being blown down, however, they are not easily made to stand again, and then 3 at least are required to be set against each other; but whatever trouble the re-setting them should create, they should not be allowed to lie on the ground, and it will be found that a windy day dries them very quickly, and secures their winning.

Rye may be reaped or mown in the same manner as the other cereal crops. Its straw, being very tough, may be made into neat slim bands. It usually ripens a good deal earlier than the other grains; and its straw being clean and hard, does not require long exposure in the field, and on that account the stooks need not be hooded.

Beans in drills are reaped only with the sickle, by moving backward, taking the stalks under the left arm, and cutting every stalk through with the point of the sickle. When beans are sown by themselves straw ropes are required for bands; but when mixed with pease, the pea-straw answers the purpose.

Beans are always the latest crop in being reaped, sometimes not for weeks after the others have been reaped and carried. In stooking, bean-sheaves are set up in pairs against one another, and the stook may consist of 4 or more sheaves, as is thought most expedient in the circumstances for the winning of the crop, the desire being to have them won as soon as possible, to get the land sown with wheat.

Pease are also reaped with the point of the hook, gathered with the left hand, while moving backward, and laid in bundles, not bound in sheaves, until ready to be carried, and are never stooked at all.

-- Henry Stephens, 1852

|

| Sheaves of Wheat in a Field, Vincent Van Gogh, 1885 |

Sources:

The book of the farm: detailing the labors of the farmer, steward, plowman, hedger, cattle-man, shepherd, field-worker, and dairy maid, Volume 2, by Henry Stephens, 1852,

Chapter 34 (page 373 onward)

Sheaves of Wheat in a Field, by Vincent Van Gogh, 1885

Place of creation: Nunen / Nuenen, Netherlands

from http://www.wikipaintings.org/en/vincent-van-gogh/sheaves-of-wheat-in-a-field-1885