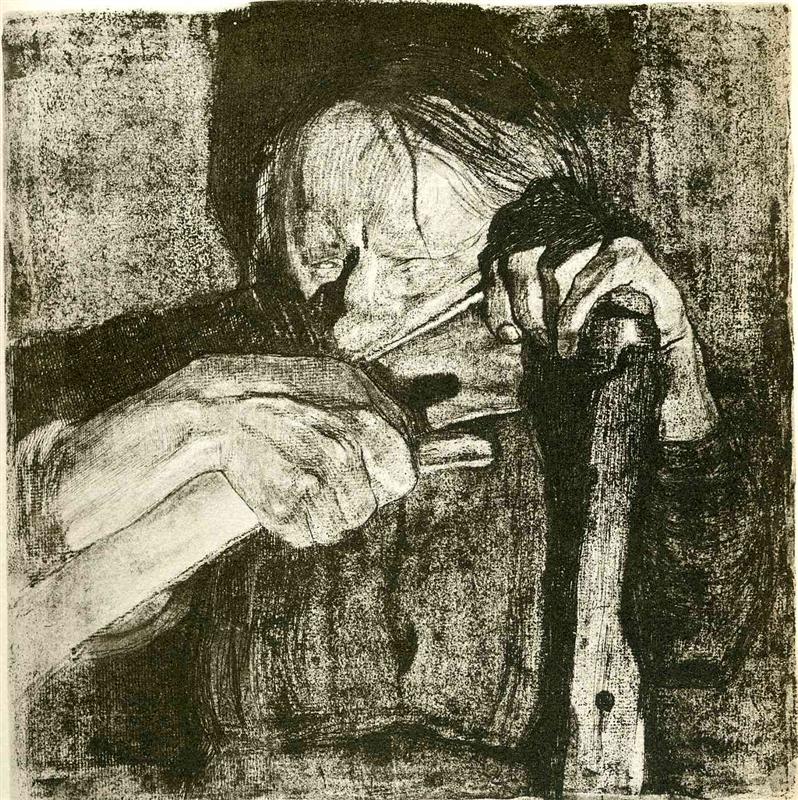

Diagonal line of 23 mowers

Detail of painting "Country around Dixton Manor", 1715

The incomparable Hay in Art website by Alan Ritch has a detailed description of the early eighteenth century painting titled "Country around Dixton Manor". Some quotes:

Careful examination revealed a peaceful army of at least 133 people (71 male, 62 female) waging a cheerful collective campaign to bring in the hay...

Meticulous attention to detail... a visual encyclopedia of haymaking...

Wagon teams of four horses and two drivers...

Work groups of five women rakers with one male forker... no fewer than 46 women with rakes, some resting, most working...

John Harris, in the Observer Magazine (4 November, 1979, p.60) called this painting "one of the most evocative pictures in the whole of English art. There is nothing like it either in its day or at any other time.."

Alan Ritch closely studied the original painting at Cheltenham and his descriptions can be found here, along with details reproduced from the painting.

An article titled "The Dixton Paintings" was written by Jane Sale and published in Gloucestershire History (1992).

A copy of the 8-page article can be downloaded here.

In an essay titled "Art and agrarian change",

Hugh Prince writes that Dixton Manor Haymaking is

...a highly unusual estate painting... The artist does not depict the country house as the center of its world... The haymaking scene is unique in the genre of prospect painting in focusing on a working field... If the artist has accurately enumerated the scene, more than half the able-bodied people of the village are out in the field [based on a historical reference to the village population in 1712]... Operational efficiency is achieved through the division of labour and the whole effort is co-ordinated under the eye of the squire...

Quoted from The Iconography of Landscape, edited by Cosgroves and Daniels, 1988, preview available here.

More recently, an episode of the BBC television series Talking Landscapes used this painting to "help uncover an Ango-Saxon agricultural revolution." The landscape should look familiar:

Photo from BBC Four series Talking Landscapes, Episode 6 of 6, "...in which Aubrey Manning sets out to discover the history of

Britain's ever-changing landscape. Clues from the local art gallery, a

spot of ploughing and a flight with a local pilot help uncover an

Anglo-Saxon agricultural revolution." [Broadcast in 2012]

This episode seems to be currently unavailable for viewing, but the transcript can be read here in the format of the subtitles for the programme. Some excerpts from the first 10 minutes of the 30-minute episode:

For 250 years, agricultural revolutions have cut through these fields. What could possibly remain of their history? On my first morning, I called on archaeologist Julian Parsons. He told me to meet him at the Cheltenham Art Gallery, where there is a landscape painting completed just before the great agricultural revolution. It's known as the Dixton Harvesters. It's a remarkable picture....

So the landscape, like the communities, was transformed by the agricultural revolution? You would think so, but if you see this view today, it has many similarities with this painting. That afternoon, I persuaded Julian to take me there... Julian insisted we find the exact spot where the painter stood nearly 300 years before...

That's the old hedge. So just where those sheep are, they cut the hay. The grain of the land, the line of the hedges, is exactly the same. Even the new hedges fit into the older pattern. That's quite extraordinary.

All that revolution, the depopulation, but the land has held its pattern. New hedges had appeared in between, but the outlines of this landscape, its fields and tracks, had hardly changed since the painter stood here in 1715.

But if this landscape wasn't created around modern agricultural machinery, what was it created for? Down in the fields themselves was a clue - a pattern of long, curving humps and hollows. Julian said it was ridge and furrow. Before recent powerful ploughs, there had been much more. This, he said, is the secret of this landscape.

That evening, we went to Gloucester to see a collection of aerial photos taken 50 years ago, before the heavy modern ploughing had begun... If you look behind the boundaries, you'll see these very faint lines, which is the ridge and furrow of the medieval field system... In this area, this was the way the land was farmed from the early medieval period... The amazing thing is how extensive this is. It's everywhere. Everywhere is ridge and furrow... a medieval farming system dating back long before the agricultural revolution.

What is this ridge and furrow and how was it made? ...The aim was to bunch up the soil in the middle and have drainage down the side... Rather different from the modern concept, which is a big flat field... You get the advantage of the drainage as well. That's how you get the waves in the landscape. Each wave is someone's piece of ground... It looks as though the ridge and furrow began because medieval fields were divided into strips, each farmed by an individual farmer. And as each one worked with his medieval plough, it piled the soil up into a ridge...

Sources:

Dixton Manor haymaking: a visual encyclopedia, Hay In Art: A collection of great works of hay. Alan Ritch, July 24, 2004

"The Dixton Paintings" article by Jane Sale, Gloucestershire History #6 (1992)

Essay titled "Art and agrarian change" by Hugh Prince, appearing in The Iconography of Landscape: Essays on the Symbolic Representation, Design and Use of Past Environments, edited by Denis Cosgrove and Stephen Daniels, Cambridge University Press, 1988

BBC Four television series Talking Landscapes, Episode 6 of 6, The Vale of Evesham, with Aubrey Manning, Julian Parsons, John Hoyell, Charles Martell... broadcast 14 Aug 2012. Subtitles appear at http://tvguide.lastown.com/bbc/preview/talking-landscapes/6-the-vale-of-evesham.html

.jpg)